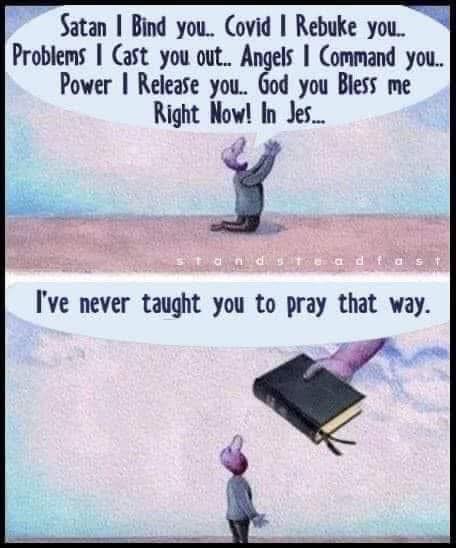

And this, Children, is all we need to know about Spirit vs. System. Otherwise understood as, “why I left the party” – the church, that is.

Consider this opinion: A Southern Baptist minister, the father of the person who wrote “Shine,” confirms that “Shine” was not “a religious song.” Rather, it was about “searching, longing … spirit, not scripture.” ( link )

At some point, I finally realized that for me, Protestantism was more about worshiping the message (sermon), the construct (Pastor, church), and the material (Bible) than about communion (worship) with Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

And if I were to offer an opinion, that’s why my church today (an Eastern Orthodox flavor) has grown significantly over the past 5 or 6 years. It is because the new folks joining have experienced something similar. At least, according to what they’re telling me.

But notice these subtle bits: in classical Christian theology, especially in Eastern Orthodoxy:

- The Son is the living Word (John 1:1), not the printed text.

- The Spirit is the life-giver, not the book.

- Scripture is inspired by the Spirit, but it is not identical to Him.

In my Baptist tradition, I eventually noticed something important. The Bible was being seen as the third entity in a quasi-trinity construct of sermon–pastor–Bible. At the same time, I noticed that the Spirit became secondary, if not unnecessary, through the same viewpoint.

The text, in function, replaced the living Spirit. Which is exactly what has happened in some circles. So, I left the church when I realized I was subtly being taught to relate to:

- A system

- A message

- A material object

instead of:

- A living Father

- A living Son

- A living Spirit

Eventually, years later, I learned about Orthodoxy and planted my feet there. In other words, I moved from mediated abstraction to participatory communion.

“The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all.”

— 2 Corinthians 13:14 (ESV)

Notice what we can glean from the scripture above:

– Grace (Son)

– Love (Father)

– Fellowship (Spirit)

In other words, what I discovered in the interim was the Spirit is not merely an idea or inspiration; He is the agent of participation.

For some people, including me many years ago, that concept wasn’t truly biblical: I viewed the Bible as my primary focus of worship, and the church was my participation.

The Subtle Shift Towards Idolatry

I worshiped the Bible, the pastor, and the church itself. It wasn’t just a religious idea either – church participation was essentially my religion. Therefore, the notion that the Holy Spirit is the agent of participation didn’t fit within my paradigm of “The Church,” nor did it resonate with me personally.

I learned, and adopted a belief system that asserted this: the only way to be assured one was consistently “right with God”, was to read the right thing (the KJV), believe the right thing, therefore enabling one to do the right thing, and ultimately, be right with God.

What I fell into was common category collapse, and idolatry. However, the Logos is:

– Eternal

– Personal

– Divine

– The Second Person of the Trinity

Contrasted with where I was:

– The Bible is not eternal (past/present/future – it came into being)

– The Bible is not a divine person.

– The Bible is not incarnate.

– The Bible did not rise from the dead.

But …

– The Word became flesh.

– The Word did not become a book.

– And an anthology (a Book) did not become the Word.

Those distinctions are absolutely foundational in historic Christianity.

It Begins with Subtle Notions, and then Idolatry

- Jesus is the Word.

- The Bible is the Word of God.

- Therefore, the Bible is Jesus.

But those two uses of “Word” are not identical.

- “Word” (Logos) in John 1 refers to a divine Person.

- “Word of God” as applied to Scripture refers to inspired revelation.

Conflating them turns a witness (the Bible) into the thing witnessed (Jesus). The problem? That is not a small mistake. That’s a theological category collapse mixed with confusion.

Biblical idolatry is not merely bowing to an object; it is:

- Locating ultimate authority in something created.

- Making a mediator (of salvation) other than Christ.

- Treating a derivative thing as the source of life (the proper position).

Paul says people

“… exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images”

— Romans 1:23, ESV

Notice: an exchange takes place.

Idolatry is a displacement; it is an exchange of one thing for another.

How the System Develops

The system typically develops like this

Step 1 — Absolute Textual Authority

“The Bible is the final authority.” sola Scriptura.

So far, that is traditionally orthodox (following or conforming to the traditional or generally accepted rules or beliefs)

Step 2 — Interpretive Necessity

But the Bible requires interpretation. So practically:

- Pastor = Authorized interpreter.

You’ve heard this before: we encourage everyone to find a “good, Bible-teaching Church.”

Step 3 — Delegated Conscience

And once we find that church and perhaps the correct translation of the Bible, we fall into the trap where what is caught becomes more important than what is taught.

As congregants, we delegate our Conscious, we learn:

- To trust the pastor’s reading.

- To measure spirituality by agreement.

- To treat deviation as rebellion.

And viola: at this point, the structure is active, and it becomes idolatrous when these shifts occur:

Instead of: God → Christ → Spirit → You,

It becomes: Bible → Pastor → You

By this time, we don’t even notice what has disappeared. Instead of living in the mediation of Christ through the Spirit, the Spirit is functionally replaced by explanation, good sermons, and proper interpretation of sola Scriptura. It is replaced by the Bible and its interpretations. Hence, the necessity of a good, bible-teaching church.

We replace worshiping the Trinity with worshiping the interpretation and, by necessity, its surrounding constructs – including the Bible itself.

Then Vs. Now

In historic Trinitarian Christianity, salvation is participatory and ongoing:

- The Father sends the Son.

- The Son becomes incarnate.

- The Spirit unites us to the Son.

- Through union with the Son, we participate in the life of the Father

Most people understand salvation as I was saved, I am being saved, and I shall be saved.

That’s dynamic, relational, mystical, sacramental, and continuous. The Spirit is not an idea. The Spirit is the one who makes Christ present, every day, all the time.

John 14:26 (Listen)

But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you.

(ESV)

Essentially, what I’m saying is the Spirit’s mediating role was displaced, and what filled the vacuum was

- Explanation.

- Interpretation.

- Correct doctrine.

- Right exegesis.

Making the structural shifts from

- Christ → Spirit → Participation

to

- Text → Interpretation → Understanding

What’s Missing from the Construct?

- Union

- Communion

- Ontological participation

The Spirit’s role is not to explain Christ. The Spirit’s role is to unite us to Christ.

Explanation is not mediation. Understanding is not union. Agreement is not communion. That’s the thing missing, the disappearance and emptiness we’ve all experienced but didn’t know how to describe or explain.

For some of us, it transformed into a sense of legalism. Maybe some of us filled the gap with Bible reading. But if you’re a legalist like I was, then you’re not reading the Bible to commune with God: you’re reading it to learn proper doctrine so you can stay out of trouble, out of way of God the Mighty Smiter.

Maybe, if you’re like me, you replaced it with prayer. But having never been illuminated to our Father’s conversational desires, you ended up just making a prayer a checklist of urgent begging.

So, in feeling and believing that we must be right and act appropriately, we urgently searched for the right church, the right teaching, and the right Bible to ensure our right position and acceptableness before God.

In actuality, this is where we landed

| What we Lost | What we found |

| Union was replaced with agreement | Instead of being in Christ, believers are measured by whether they affirm correct propositions about Christ. |

| Communion was replaced with comprehension | Instead of sharing in Christ’s life, the goal becomes mastering theological content. |

| Ontological participation was replaced with cognitive accuracy | Transformation is assumed to occur through right thinking rather than Spirit-mediated incorporation into Christ. |

| The Spirit’s presence was replaced with methodological precision | Confidence shifts from divine indwelling to hermeneutical technique. |

| Illumination was replaced with information | The Spirit’s role in making Christ present is quietly reduced to helping us understand the text correctly. |

| Corporate participation was replaced with sermon centrality | Gathered worship becomes primarily instructional rather than participatory in Christ’s life. We sit down, shut up, pay up, get up, and leave. |

| Sacramental reality was replaced with memorial symbolism | Means of grace become reminders rather than Spirit-mediated participation. |

| Spiritual formation was replaced with doctrinal alignment | Maturity is defined by theological correctness rather than increasing participation in divine life. |

| The living voice of Christ was replaced with historical reconstruction | The text becomes a closed historical artifact rather than the Spirit’s present instrument of communion. |

| Dependence was replaced with system | The Spirit’s active mediation is functionally replaced by confessional structures and theological systems. |

| Transformation was replaced with moral effort | Instead of participation in Christ’s life, change is pursued through discipline and willpower. |

| Mystery was replaced with control | Where participation implies divine mystery, interpretation offers mastery and containment. |

Why Sola Scriptura Can Drift this Way

In its most careful form, sola Scriptura simply says Scripture is the final norm. But functionally, in some contexts, it erodes and transforms its environment. It instills something else, things that are subtly caught:

- Scripture is the only reliable authority.

- — Therefore doctrine must be derived by interpretation.

- — Therefore, the central act becomes a correct explanation.

- — Therefore, spiritual maturity becomes doctrinal precision.

- — Therefore, the central act becomes a correct explanation.

And gradually:

- The pulpit becomes central.

- The sermon becomes the high point.

- Interpretation becomes sacred.

The Spirit’s experiential mediation fades into the background. It’s never really denied, not outright. But replaced? Absolutely.

But REALLY? What Has Disappeared?

… because nothing looks gone.

- We still say “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

- We still read Scripture.

- We still pray.

But what may disappear is:

- The sense that salvation is participation in divine life.

- The sense that worship is entering heavenly reality.

- The sense that the Spirit is actively uniting us to Christ in the present.

- Instead faith becomes …

Correctly thinking about what Christ did.

- Rather than:

Being united to what Christ is.

And that is a massive theological and doctrinal shift that happened right under our noses – most notably, kicked off during the Reformation.

This is also why we aren’t bothered by hearing the same evangelical message again and again. “That was a great sermon, Pastor…” We’ve heard it ten times, but it’s still great – because it forces us to think correctly about what Jesus did.

Worship Shifted from God to Constructs

I’m right about something psychologically inevitable, and don’t miss this:

When interpretation becomes central,

then the structures that guard interpretation become sacred.

- The theological system.

- The pastor who preserves it.

- The institution that protects it.

And disagreement becomes an existential threat.

Which is why (precisely why) there are so many protestant denominations and churches. At this point, we’re not defending communion with the Trinity, as we did during the Ecumenical Councils, where the Nicene Creed was developed. Today we’re defending a system of explanation. And that can absolutely become a form of worship, aka, “the creature, rather than the Creator.”

A Necessary Nuance

But there’s a balance: scripture itself speaks of:

- Teaching

- Sound doctrine

- Guarding the faith

So, the solution is not anti-doctrinal, regressive, or anti-theological. The danger isn’t explanation, sermons, or Bible translations. The danger is when explanation replaces participation.

The early Church never separated doctrine from worship.

Doctrine safeguarded participation.

It did not substitute for it.

I’m not simply critiquing Protestantism, Catholicism, or Orthodoxy. I’m asking something deeper: what is Christianity fundamentally?

Is it:

- Right interpretation of sacred text?

Or is it:

- Participation in the life of the Triune God?

If it is the latter, then anything that reduces faith to interpretive correctness — even with good intentions — risks hollowing out its center.

“the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life.”

— 2 Corinthians 3:6 (ESV)