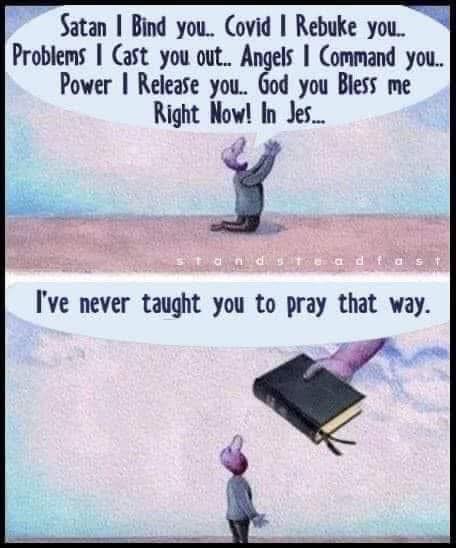

In this blog, I am presenting a rebuttal to the “God never taught you to pray that way” meme. I will attempt to remain grounded in Greek command language, and the juridical semantics of the Hebrew term תפילה (tefillah).

The aim is not to defend every phrase in the prayer depicted in the meme, but to reject a false dilemma that underlies the meme itself. I will argue that directive speech can be legitimate when exercised within delegated authority and that biblical prayer cannot be reduced to polite requests or the normative begging posture often taught by church leaders or depicted by popular media.

The Meme’s False Dilemma

While the meme is rhetorically clean and theologically satisfying to many, it rests on a major unstated assumption:

Prayer must be fundamentally petitionary (begging) and command-form speech is therefore inherently unbiblical.

That assumption does not survive contact with:

- the Greek grammar of Jesus’ commands

- how authority actually functions in the New Testament world

- the Hebrew semantics underlying what Scripture calls “prayer”

Part I: The Greek Frame

ἐντέλλομαι (entellomai, “to command or charge”) and Delegated Authority

Jesus Explicitly Frames Discipleship as Obedience to Commands

In Matthew 28:20, Jesus commissions the apostles to teach:

- πάντα ὅσα ἐνετειλάμην ὑμῖν

- (panta hosa eneteilamēn hymin)

- “everything I commanded or charged you.”

The verb derives from ἐντέλλομαι (entellomai), which means to command, charge, or direct with authority. This verb belongs to contexts where directives are meant to be executed, not merely remembered. The Great Commission is therefore not framed as “teach them what I said,” but “teach them what I charged you to obey.”

This implies several things:

- Authority flows from Jesus downward

- The disciple is expected to act, not merely speak

- The charge includes imitation of authoritative practice, not just verbal doctrine

This is where the meme’s critique becomes overbroad. It treats prayer posture as though Jesus authorized only deferential asking, when Jesus also authorized commissioned execution under his authority.

Delegated Authority Is Explicit: ἐξουσία (exousia)

Just prior to using ἐνετειλάμην (“I commanded” or “I charged”), Jesus grounds the entire mission in this declaration:

- ἐδόθη μοι πᾶσα ἐξουσία

- (edothē moi pasa exousia)

- “All authority has been given to me.” (Matthew 28:18)

ἐξουσία (exousia) refers to authority or delegated power. This is the operating logic of the commission. Jesus possesses authority and delegates action under that authority.

In ancient command structures such as military, household, and legal systems, a subordinate does not request permission for every operational step. He executes within the scope of what has been authorized. That does not mean the subordinate outranks the superior. It means he functions as an agent.

So the relevant question is not whether command-form speech is always wrong. The relevant question is this:

Is the speaker acting as a delegated agent under Christ’s authority, or as a sole originator of power?

Rabbinic Authority and Charismatic Authority Are Not Opposites

Modern debates often frame this as a binary, one or the other argument:

- Rabbinic authority is textual, interpretive, and disciplined

- Charismatic authority is experiential, miraculous, and power-oriented

This opposition is anachronistic when applied to Jesus and the apostles.

In first-century Jewish life, disciples often functioned as authorized agents under shaliach logic. A disciple was expected to:

- learn not only the rabbi’s words but the rabbi’s way

- imitate patterns and methods

- represent the teacher’s authority within the teacher’s domain

Jesus functions as both a rabbinic teacher shaping interpretation and ethics, and a charismatic authority exercising power over illness and hostile spiritual forces.

Crucially, Jesus treats that power as delegable (e.g., commissioning of the 70/72). He authorizes his followers to act under his commission.

Charismatic action, when delegated and bounded, is not anti-rabbinic. It becomes an expression of rabbinic agency. Disciples execute the teacher’s charge.

Jesus Himself Used Directive Speech

A central weakness in the meme is the implication that Jesus did not model command-form engagement with the world.

Yet Jesus repeatedly uses directive speech toward non-divine targets:

- to sickness: “Be clean.”

- to spirits: “Come out.”

- to nature: “Peace, be still.”

- to bodies: “Get up and walk.”

These are performative speech acts. The language is intended to effect change, not merely to request it. Jesus never begs the Father to heal a person in these encounters.

Observers explicitly identify this mode of speech as authority. “He commands even the unclean spirits, and they obey him” (Mark 1:27).

If the Great Commission’s commands include embodied imitation, then directive speech, when exercised as delegated authority, cannot be dismissed as un-Jesus-like.

The real debate is not directive speech versus biblical prayer. The debate is directive speech within scope versus directive speech that claims self-originating power.

The Real Fault Line: Grammar Toward God Versus Standing Under God

Critics often focus on an imperative phrase such as “God, you bless me right now.”

Two clarifications are essential.

Imperative Grammar Is Not Automatically Theological Domination

In biblical prayer, imperatives toward God are common, especially in the Psalms. “Hear,” “remember,” and “listen” appear frequently. The imperative form can express covenantal urgency, confidence, and appeal without implying metaphysical superiority.

Grammar alone does not settle the issue.

The Real Issue Is Attribution of Authority

The legitimate correction is not:

- “God never taught you to pray that way.”

- The precise correction is:

- “You were never authorized to speak as though authority originates in you.”

The meme collapses this distinction, assuming readers will infer it – hoping you will “catch” a meaning that is not there. The New Testament framework of authority does not allow that collapse.

The Hebrew Frame: Prayer Is Not Primarily Begging

When we move beneath the New Testament into Israel’s conceptual world, the meme’s assumption collapses further.

Hebrew Has No Single Word Equivalent to “Prayer”

Biblical Hebrew distributes what English collapses into “prayer” across multiple verbs and postures:

- crying out

- appealing

- seeking favor

- requesting

- interceding

- arguing a case

- covenantal complaint

- confession

English flattens this diversity. Hebrew does not.

The Root פלל (palal)

פָּלַל (palal) carries the sense of intervening, arbitrating, judging, or interposing oneself. The noun תְּפִלָּה (tefillah), commonly translated “prayer,” frequently carries juridical and covenantal overtones.

The primary verbal form for praying appears in the Hitpael stem:

הִתְפַּלֵּל (hitpalel)

Hitpael often indicates reflexive or self-involving action. To pray, in this sense, is to place oneself into the matter before God. It is active positioning, not passive piety.

This juridical sense does not exclude devotion or dependence. It defines the structural posture in which devotion occurs.

Covenant Complaint and Appeal

Hebrew prayer frequently includes pleading, lament, protest, argument, and appeal to covenant faithfulness. This is why prayers such as Psalm 44 or Habakkuk 1 can sound confrontational in English while remaining fully legitimate.

Biblical prayer is not defined by a single tone or grammatical mood. It is defined by covenantal standing and alignment with rightful authority.

Reframing the Debate: Prayer as Standing and Delegation

When the Greek and Hebrew frameworks are brought together, a clearer picture emerges.

The Greek lens shows:

- Jesus commissions with ἐντέλλομαι

- the commission is grounded in ἐξουσία

- disciples act as delegated agents

The Hebrew lens shows:

- prayer as tefillah is covenantal interposition

- praying as hitpalel is entering the matter before God

Therefore, the meme’s categorical dismissal fails.

Command-form speech toward hostile forces or conditions is not automatically illegitimate when practiced as delegated authority under Christ.

Bold speech toward God is not automatically illegitimate because Hebrew prayer often operates covenantally and juridically.

The decisive test is standing and attribution:

- Are you positioned under God’s authority?

- Are you acting as an authorized agent, or as a self-originating source?

“In Your Name”: Why Formula Without Standing Fails

In Matthew 7, speakers appeal to Jesus:

“Did we not prophesy in your name, cast out demons in your name, and do mighty works in your name?”

Jesus responds:

“I never knew you.”

The issue is not activity, grammar, or terminology. It is standing.

They speak toward Christ but are not positioned under Christ’s authority.

“In your name” is not a formula. It is a relational and legal status. Invocation without recognition fails.

Final Synthesis

Prayer and action are not validated by formulas.

Authority is not validated by results.

Standing is not created by invocation.

The biblical framework consistently returns to the same axis:

Position before performance.

Relationship before results.

Delegation before declaration.

That is where the meme fails, and that is where Scripture insists the conversation must remain.

The Lord’s Prayer

Framing Principle

The Lord’s Prayer does not teach prayer as begging. It teaches prayer as positioning under authority, followed by authorized engagement.

This is exactly what both models expect.

The Two Models, Stated Precisely

Hebrew Model (תְּפִלָּה / הִתְפַּלֵּל)

Prayer is:

- covenantal standing before rightful authority

- juridical orientation

- entering the matter under God’s rule

- appeal grounded in relationship, not leverage

Core question: On what standing do I speak?

Greek Model (προσεύχομαι)

Prayer is:

- directed speech toward God

- relational orientation

- acknowledgment of dependence

- alignment with divine will and authority

Core question:

Toward whom am I directing myself, and in what posture?

The Lord’s Prayer satisfies both questions simultaneously, line by line.

Line-by-Line Analysis

1. “Our Father in heaven”

Greek consistency

- Direct address toward God (pros + euchomai)

- Establishes relationship before request

- Dependence is explicit

Hebrew consistency

- Covenant identity is declared first

- “Father” implies standing, not distance

- This is court entry language, not supplication

Key point

No request is made yet. Position precedes petition.

2. “Hallowed be your name”

Greek

- Orientation toward God’s holiness

- Reverence establishes relational posture

Hebrew

- Sanctifying the Name is covenantal allegiance

- The speaker aligns with God’s reputation and authority

- This is a loyalty declaration

Key point

This is not asking God to become holy.

It is placing oneself under God’s holiness.

3. “Your kingdom come”

This is imperative grammar, directed toward God.

Greek

- Imperatives in prayer are permitted

- The direction remains toward God, not away from Him

Hebrew

- This is covenant invocation

- Calling for the manifestation of God’s rule

- Equivalent to covenantal appeal for rightful authority to act

Key point

This is not domination.

It is invoking rightful authority.

4. “Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven”

This line governs everything that follows.

Greek

- Explicit submission of desire to God’s will

- Prevents self-originating authority

Hebrew

- Aligns the speaker with the heavenly court

- Earth is petitioned to conform to divine order

- The speaker positions themselves inside that alignment

Key point

Nothing in this prayer authorizes action outside God’s will.

This is the scope clause.

5. “Give us today our daily bread”

Greek

- Legitimate petition

- Dependence is acknowledged

Hebrew

- Covenant provision language

- Echoes wilderness provision

- Appeal based on relationship, not merit

Key point

Request flows from standing, not desperation.

6. “Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors”

Greek

- Relational repair

- Moral alignment with God

Hebrew

- Explicit juridical language

- Debt, forgiveness, obligation

- The speaker submits themselves to covenant standards

Key point

The petitioner places themselves under judgment, not above it.

This is hitpalel in action: self-involving positioning.

7. “Do not lead us into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one”

Greek

- Directed plea for protection

- Dependence acknowledged

Hebrew

- Appeal for covenant safeguarding

- Recognition of hostile forces

- Request for rightful authority to intervene

Key point

This is not passive fear.

It is appeal to the rightful protector.

8. Doxology (traditional):

“For yours is the kingdom, the power, and the glory”

Greek

- Reorients all authority to God

- Ends where it began: with God’s supremacy

Hebrew

- Explicit attribution of authority

- Prevents any misreading of earlier imperatives

- Reinforces non-self-originating power

Key point

Authority is named, located, and returned to God alone.

Structural Summary

The Lord’s Prayer follows a deliberate architecture:

- Establish covenantal standing

- Align with God’s authority and will

- Invoke rightful rule

- Make bounded requests

- Submit to moral accountability

- Acknowledge dependence and threat

- Reaffirm God as sole authority source

This is textbook Hebrew tefillah and Greek proseuchomai operating together.

Why This Matters for the Debate About “Command-Form Prayer”

The Lord’s Prayer contains imperatives:

- “Hallowed be”

- “Your kingdom come”

- “Your will be done”

Yet no one claims it is arrogant or illegitimate.

Why? Because:

- authority is not claimed by the speaker

- standing is covenantal, not performative

- will and scope are explicitly bounded

- attribution is consistently returned to God

This is the same framework as outlined earlier.

Final Synthesis

The Lord’s Prayer does not teach:

- prayer as begging

- prayer as technique

- prayer as self-originating declaration

It teaches:

- prayer as position before authority

- prayer as alignment before action

- prayer as delegated dependence

Which means:

The Lord’s Prayer is not a counter-example to bold or directive prayer.

It is the governing model that determines whether such prayer is legitimate or illegitimate based on standing, delegation, and attribution, not on grammar or tone.

That is why it coheres cleanly with both the Hebrew and Greek models of prayer.

Be aware of what teachers expect you to catch vs. what they actually teach.